Glassholes, Symmetry, and Facial Indication

Google Glass has taken a bit of a beating in the press in the last year since its announcement in February of 2013. Writer Mat Honan says his wife and fellow employees at Wired Magazine didn’t care for his wearing the device. He notes being called names such as “nerd” and “bluedouche” was a detraction. Name calling becomes a curious phenomenon to me when employees at Wired Magazine take a condescending stance regarding a technology product. Perhaps worse for Google Glass, is the anecdotal evidence that even Google employees are wearing them less. But in my perusal of the criticism of Google Glass, I’ve seen no mention of the fact that they are asymmetrical and have none of the culturally established indicators for devices of their ancestor’s kinds—not as a UI, but as a recording device. Both of these things may sound like oddball objections, but then design is always in the details.

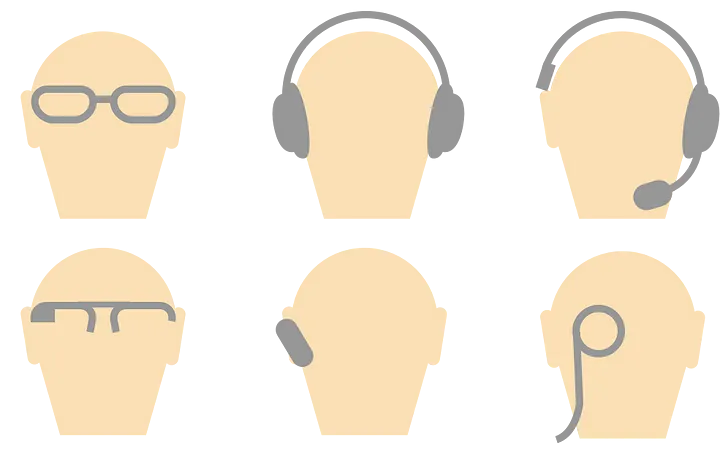

I’m ambivalent about predictions of Google Glass’s success or demise. I am all for technology that alleviates my already bad eyes. As a “sight-impaired” individual, I’m less concerned with Google Glass than I am with contacts that will give me “zoom” features! I mean, if contacts that zoom are a possibility on the horizon then the technological silk road appears to be traveling to a place where the Internet is always in front of us, becoming merely part of our visual field. It’s not one product I’m concerned about here, but the design of wearable “facial interface devices”—although “head interface devices” might be more appropriate when you consider bluetooth headsets and headphones. The generic terminology on touchscreens seems settled, so what are screens activated by eyes?— glancescreens? Anyway, the nomenclature of this branch of tech notwithstanding, and to put it colloquially, designers working on objects that go on your face should consider some minor neurological constraints before wrapping up their CAD designs. So far, the designs of facial (head) interface devices has been a mixed bag with regard to what neurology tells us about human facial computation.

Some neurology regarding facial beauty

Humans not only possess an inherent attraction to symmetry in faces, they tend to make additional social judgements based on those intuitions. Mind you, it is important here to know that symmetry does not equal beauty in the least—there are many factors at play where beauty in human faces is concerned—symmetry is an important one and linked to genetics. Since the 1990s, it has been argued that facial symmetry (and finding facial symmetry attractive) is an evolutionary adaptation and a signal of good genetics in potential mates.

Human judgements regarding facial symmetry as attractive are cross-cultural, and the adaptation may be older than our species as it appears in other species as well. That subconscious reaction to symmetry in a human face is built-in; you won’t notice that you’ve noticed the symmetry of a person’s face. The reaction is a deep computation in the human brain resulting in a sense of attractiveness or not. But given that we are conscious beings and tend to like to create linguistic explanations for things we intuit, we are also likely to place other kinds of judgements on top of intuitions like facial symmetry, such as thinking that a beautiful person seems honest or trustworthy among many other stereotypical judgments.

So, why rock the evolutionary boat with our designs for facial interface devices? As designers, we may think that novelty trumps tradition here because we think we are dealing with a whole new class of devices. I would argue that while the computational power of these devices has increased tremendously, the forms are not that new, and no amount of power in the device is going to overcome the human intuition that something is not quite right in a user sporting a device that makes his or her face asymmetrical. In brief, haven’t monocles always been douchey?

Social Indication in devices is not-so-new

Similar to the design problem of not disrupting facial symmetry is the problem of not disrupting social focus. One thing about facial interface devices that is new-ish, is their ability to indicate states of the user outwardly to people other than the user. I only see this development as “new-ish” because if we lump cameras and camcorders into the category of facial interface devices (you hold them up to your face to use them) then outward indicators—primarily big red lights that indicate when recording is happening and big lenses indicating the subject of potential recordings—has been culturally with us for several decades. This outward indication of intent/focus is equally important when a device removes our natural ability to indicate focus. Doesn’t the general disdain for wearing sunglasses indoors arise from their being used for the secondary purpose of hiding one’s focus?1

Part of the squeamishness that comes along with encountering a user of Google Glass, as opposed to someone with a camcorder or a 35mm camera, is that we know to treat someone taking our picture without permission with some disdain. With Google Glass—and bluetooth headsets to an extent—we’re not sure what the user is up to. The participant external to the device is thinking, “Are you even paying attention to me? Are you recording me?” For my part, I probably would not have a conversation with someone wearing Google Glass. Depending on my relationship with the user of Glass, I would ask them to remove their glasses or I would ignore them. My own sensibility appears to be common amongst many I’ve spoken to.

But two simple design changes would make me comfortable in changing that stance. One, add a big red light that indicates that a user is recording. It’s simple and it’s a signal that many people (at least in modern societies) would recognize.2 Two, create a design that let’s the user more easily perch the glasses on their head (you know, like we do with sunglasses) so that I can know that I have a Glass user’s full focus and attention. I would even go so far as to suggest that such a device could go one courteous step further by projecting a laser-traced box just around the portion of the world that is going to be captured pre-recording. I can foresee some shortcomings in such laser-traced indicator, but then camera flashes are far more annoying to me.

The Face is the best communication device we have

Designers should take great care in designing devices that cover any part of the face. Because of the sheer bandwidth of information that transpires in human face-to-face communication; because it took evolution hundreds of thousands of years to develop it, a designer would be wise to begin the design of a facial interface device with the premise that nothing the computer and industrial design industries have accomplished so far in interface design remotely equals face-to-face communication. To that end, take care when covering up or replacing any face-to-face interaction. I will give Google Glass some credit for trying to mostly stay out of the way, but I do not think the designers were quite cautious enough, and I definitely predict that the interface of the future in this use case will need to be abstractly and literally transparent.

1 Covering up appearances (like drug use or physical abuse or even a handicap) is another surreptitious use of sunglasses indoors, but that just means that any use of sunglasses indoors is an indicator of the user not being entirely truthful in their actions, or at the very least, somewhat socially challenged— ahemretardedahem.2 It occurs to me that I would really like to see the reactions to Google Glass from a tribe of low-technology people.